I work at the

Jožef Stefan Institute in Ljubljana, Slovenia, in the

Department of Surface Engineering and Optoelectronics. But don't let the title mislead you, I'm still a mere student. I took this job only because it sounded interesting and I have some free time to kill.

So what exactly is my job? I am studying the effect of plasma on the physical properties of polymers. More specifically, how plasma affects the surface energy of a polymer. I'm sure you have long forgotten everything about plasma and polymers, so here's a short reminder.

Plasma.

Plasma is a state of matter similar to gas, but obtaining it is not as easy. There are various types of plasma and even more ways to obtain them, but I won't get too much technical. As always, you can educate yourself by following the link to the trusty

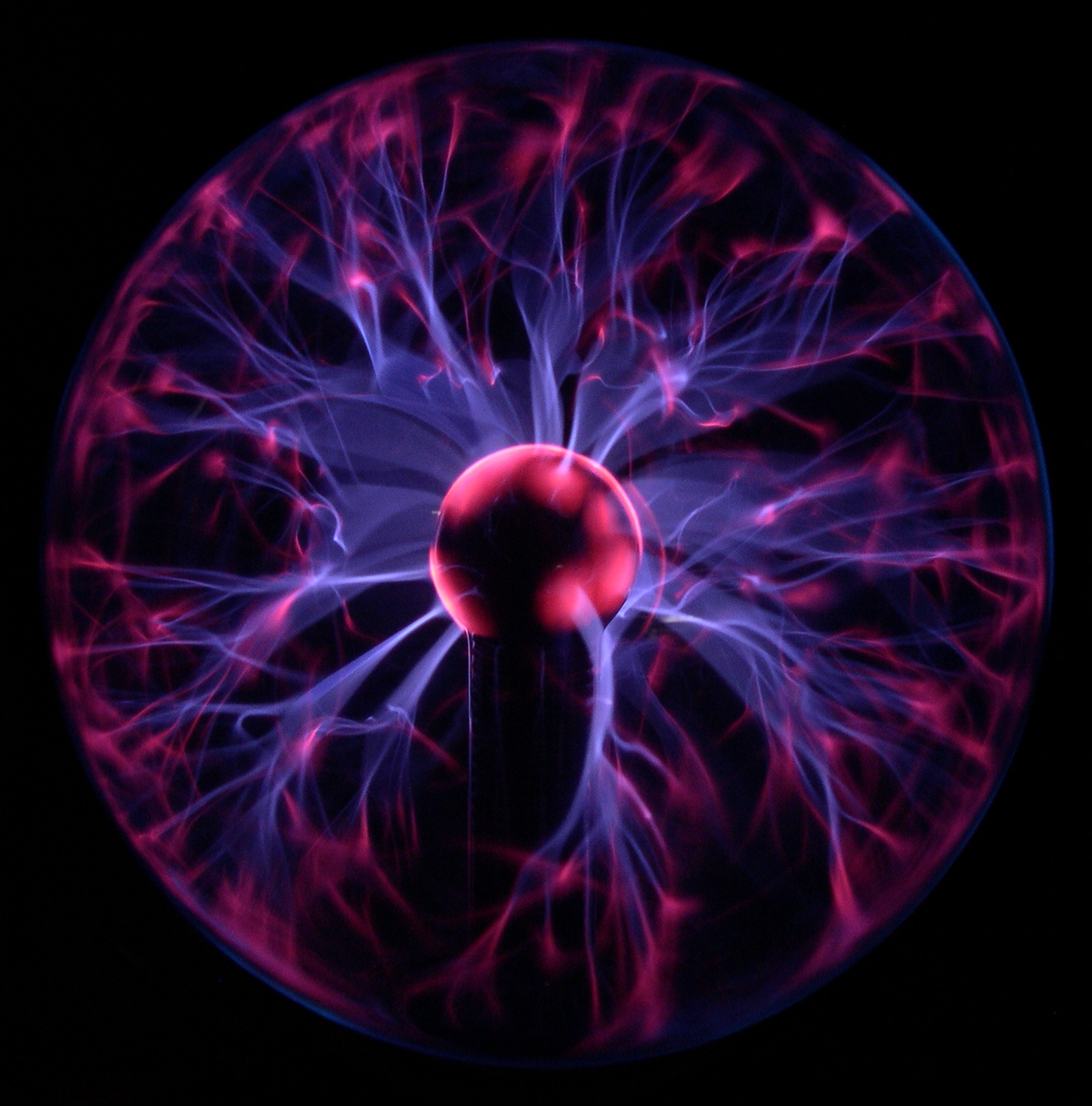

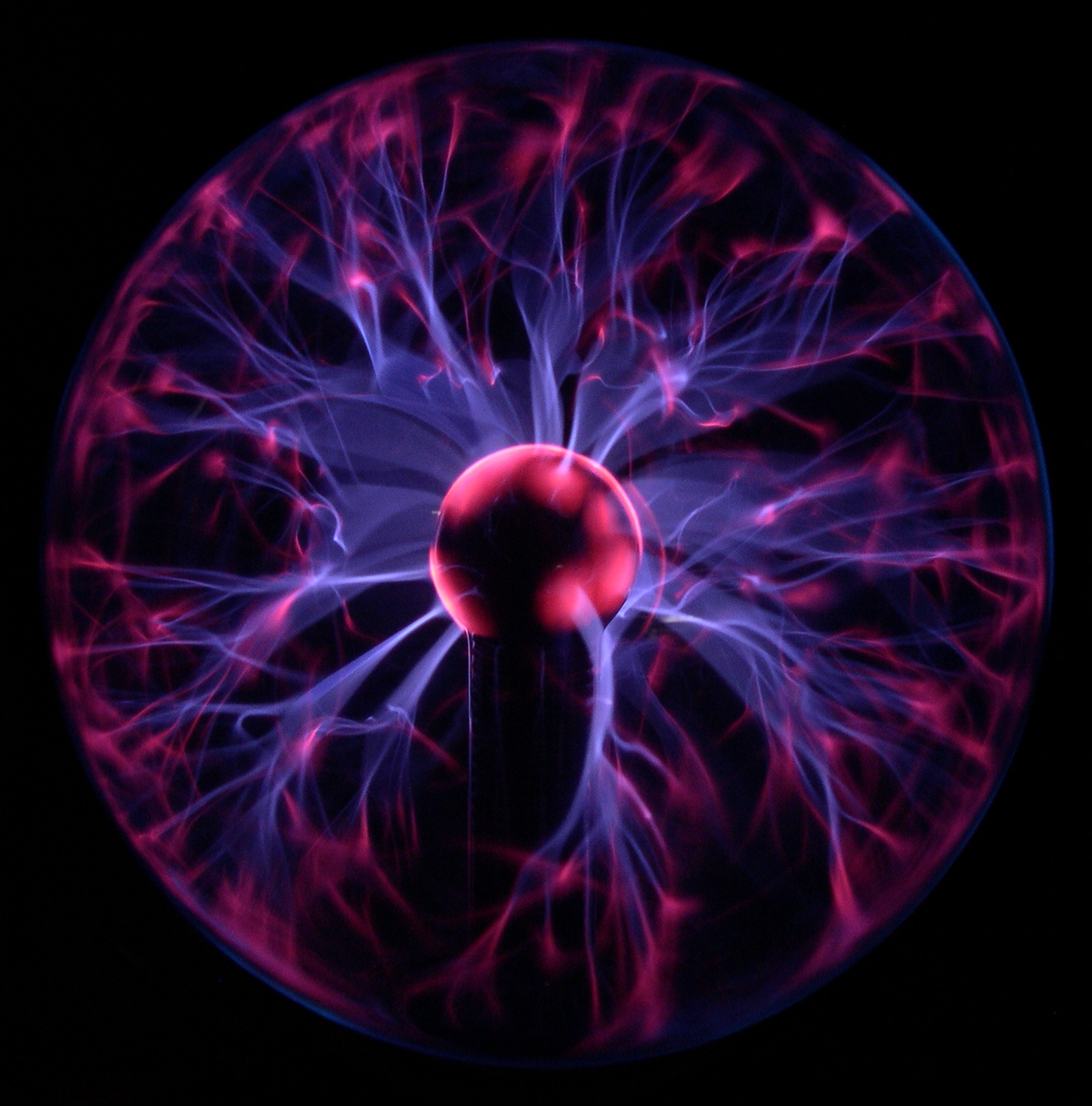

Wikipedia article. Nevertheless, you might have already come in contact with plasma without knowing it. For example, plasma lamps are in my opinion the cheapest way to generate significant amounts of plasma at home without running unnecesary risks of burning the house down or being killed by imploding glassware.

|

| More dangerous than it looks! | |

|

Plasma TVs also contain some plasma (duhh) but if it weren't in the name you wouldn't even know it's there.

And why is plasma useful?

As mentioned before, plasma TVs

(that provide the best looking picture of all technologies available to the common man.)

Also, metals and other materials can be coated, etched, cut and welded using plasma.

(Who wants to melt some rocks?)

Also, fluorescent lamps

(I still prefer the oldschool tungsten coil though.)

Also, various modern chemical analytical techniques are based on inductively coupled plasma.

(This is the kind of plasma i'm wrking with, too.)

You can't immagine a world without plasma, really.

So to obtain plasma you need a strong pulsating magnetic field. For that, you need a pulsating electrical field. Long story short, connect the plug to the wall socket. But not so fast, you will also need a vacuum pump and a chamber where your gas of choice will be rarefied. In a semi-professional laboratory it will look something like this:

|

| Close-up of the Tube with some oxygen plasma in it. Note the Coil around it - this generates the necessary magnetic field. |

|

| The Machine. On the left there is a High-Current Electric Generator that powers the Coil. Also note the open-source CubeSpawn frame. |

|

|

With all equipement provided working with plasma is a walk in the park. I just put a sample of a polymer in the tube, adjust the pressure to the appropriate level, provide some cooling if the things get too intense and then sit back and enjoy the show. After a couple of seconds the process is done and I can move to the next step - figuring out what just happened.

Surface tension and surface energy.

What is this all about? Wikipedia tries to help: "Surface energy quantifies the disruption of intermolecular bonds that occurs when a surface is created."

What? Basically, it is a physical property that tells you how strong the drops will hold on to the surface of a given material. The lower the energy, the more the drop will stick to the surface and the more flat it will be (the "flatness" is defined by the

contact angle).

|

| Different contact angles correspond to different surface energies. |

Bacause drops are usually small (I use 1 µL standard volume), a special instrument is needed for a precise determination of the contact angle. Here comes the goniometer.

|

| Advex Instruments' Surface Energy Evaluation System |

This is nothing more than a webcam with a stage where you place the sample and some wheels to adjust the focus. All you have to do is connect the goniometer to a USB port and run the provided software. You can now make some pretty pictures of your droplets, and with a simple point-and-click procedure determine the contact angle.

|

| See Software 6.0 |

Calculating the surface energy from the contact angle is a bit more complex and definitely more boring, so I will spare the details. Furhermore, everything is done automatically. Once I will have a nice large enough set of surface energy data corresponding the different pressures of the plasma and exposure times I will be able to make some pressure- and time-dependency plots. Stay tuned.